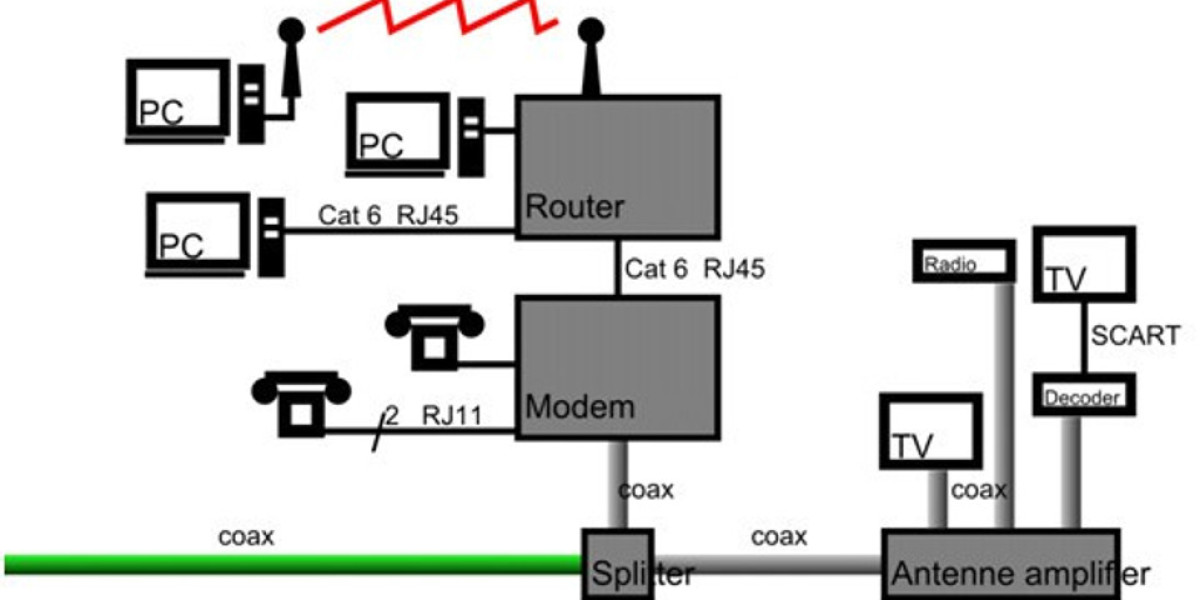

The Boulders advancement, integrated in 2006 in Seattle's Green Lake neighborhood, features a mature tree along with a waterfall. The designer likewise included mature trees restored from other developments - putting them strategically to add texture and cooling to the landscaping. Parker Miles Blohm/KNKX hide caption

Climate modification shapes where and how we live. That's why NPR is dedicating a week to stories about options for structure and living on a hotter planet.

SEATTLE - Across the U.S., cities are struggling to balance the requirement for more housing with the requirement to maintain and grow trees that help attend to the effects of climate modification.

Trees provide cooling shade that can save lives. They soak up carbon contamination from the air and lower stormwater runoff and the risk of flooding. Yet numerous builders perceive them as an obstacle to quickly and effectively setting up housing.

This stress in between development and tree preservation is at a tipping point in Seattle, where a brand-new state law is needing more housing density but not more trees.

One service is to find methods to build density with trees. The Bryant Heights development in northeast Seattle is an example of this. It's an extra-large city block that features a mix of modern apartment or condos, town homes, single-family homes and retail. Architects Ray and Mary Johnston dealt with the developer to place 86 housing units where once there were 4. They likewise conserved trees.

Architects Mary and Ray Johnston conserved more than 30 trees in the Bryant Heights development they worked on. Parker Miles Blohm/KNKX conceal caption

"The first question is never, how can we get rid of that tree," discusses Mary Johnston, "but how can we save that tree and build something special around it." She indicates a row of town homes nestled into 2 groves of fully grown trees that were in location before building started in 2017. Some grow simple feet from the brand-new structures.

The Johnstons protected more than 30 trees at Bryant Heights, from Douglas firs and cedars to oak trees and Japanese maples.

One of Ray Johnston's favorites is a deodar cedar that's more than 100 feet tall. The tree stands at the center of a group of apartment structures. "It probably has a canopy that is close to over 40 feet in diameter," he keeps in mind.

This cedar cools the neighboring buildings with the shade from its canopy. It filters carbon emissions and other contamination from the air and works as an event point for citizens. "So it resembles another homeowner, actually - it's like their neighbor," Mary Johnston states.

Preserving this tree required some additional negotiations with the city, according to the Johnstons. They had to prove their new building and construction would not damage it. They had to concur to utilize concrete that is porous for the walkways below the tree to enable water to leak down to the tree's roots.

The developer could have easily chosen to take this tree out, together with another one close by, to fit another row of town homes down the middle of the block. "But it never pertained to that due to the fact that the developer was informed that way," Ray Johnston says.

Preserving some trees in Bryant Heights needed extra settlements with the city of Seattle. Special concrete that is porous was utilized for the walkways below particular trees, allowing water to seep down to the trees' roots. Parker Miles Blohm/KNKX hide caption

Housing pushes trees out

Seattle, like lots of cities, remains in the throes of a housing crunch, with pressure to include countless new homes every year and increase density. Single-family zoning is no longer allowed; instead, a minimum of 4 units per lot should now be allowed all city communities.

The City Council recently upgraded its tree defense ordinance, a law it first passed in 2001, to keep trees on personal residential or commercial property from being reduced during development.

"Its baseline is defense of trees," states Megan Neuman, a land use policy and technical teams manager with Seattle's Department of Construction and Inspections. She says the brand-new tree code includes "limited instances" where tree elimination is enabled.

"That's actually to attempt to assist find that balance between housing and trees and growing our canopy," Neuman says. Despite the city's efforts to protect and grow the urban canopy, the most current evaluation showed it diminished by an overall of about half a percent from 2016 to 2021. That's equivalent to 255 acres - a location roughly the size of the city's popular Green Lake, or more than 192 regulation-size American football fields. Neighborhood residential zones and parks and natural locations saw the biggest losses, at 1.2% and 5.1% respectively.

Seattle says it's dealing with multiple fronts to reverse that pattern. The city's Office of Sustainability and Environment says the city is planting more trees in parks, natural locations and public rights of method. A new requirement implies the city also has to care for those trees with watering and mulching for the first five years after planting, to guarantee they survive Seattle's progressively hot and dry summertimes.

The city likewise says the 2023 upgrade to its tree protection regulation increases tree replacement requirements when trees are gotten rid of for development. It extends security to more trees and requires, for the most part, that for every tree eliminated, 3 must be planted. The objective is to reach canopy protection of 30% by 2037.

Developers normally support Seattle's latest tree security ordinance since they say it's more foreseeable and flexible than previous versions of the law. Much of them assisted shape the new policies as they deal with pressure to include about 120,000 homes over the next 20 years, based upon development management planning required by the state.

Cameron Willett, Seattle-based director of city homes at Intracorp, a Canadian property developer, sees the current code as a "sound judgment method" that enables housing and trees to exist together. It allows home builders to reduce more trees as required, he says, however it likewise needs more replanting and enables them to develop around trees when they can. "I absolutely have tasks I've done this year where I have actually secured a tree that, under the old code, I would not have had the ability to do," Willett states. "But I've also had to replant both on- and off-site."

Willett recalls one development this year where he preserved a mature tree, which needed proving that the website might be developed without damaging that tree. That likewise indicated "additional administrative intricacy and costs," he discusses.

Still, Willett states it deserves it when it works.

"Trees make much better communities," he says. "We all wish to conserve the trees, however we also need to be able to get to our max density."

But Tree Action Seattle and other tree-protection groups regularly highlight new developments where they say a lot of trees are being gotten to make way for housing. This tension comes after a terrible heat dome hovered over the Pacific Northwest in the summer season of 2021. "We saw hundreds of individuals pass away from that, hundreds of people who otherwise would not have passed away if the temperatures hadn't gotten so high," states Joshua Morris, conservation director with the not-for-profit Birds Connect Seattle. He served 6 years as a volunteer advisor and co-chair of the city's Urban Forestry Commission, which provides expertise on policies for conservation and management of trees and greenery in Seattle.

Joshua Morris, conservation director with the not-for-profit Birds Connect Seattle, served six years as a volunteer consultant and co-chair of Seattle's Urban Forestry Commission. Parker Miles Blohm/KNKX conceal caption

"We know that in leafier communities, there is a substantially lower temperature level than in lower-canopy communities, and often it can be 10 degrees lower," Morris states.

Making area for trees

Seattle's South Park community is one of those hotter neighborhoods. Residents have approximately 12% to 15% tree canopy coverage there - about half as much as the citywide average. Studies show life span rates here are 13 years shorter than in leafier parts of the city. That remains in large part due to air pollution and impurities from a close-by Superfund website.

In a cleared lot in South Park, 22 brand-new units are going in where when 4 single-family homes stood. Three big evergreens and a number of smaller trees are anticipated to be lowered, says Morris. But with some "slight rearrangements to the setup of buildings that are being proposed," Morris assumes, "a designer who has actually done an analysis of this website reckons that all of the trees that would be slated for removal might be retained. And more trees might be added."

Tree removals are enabled under Seattle's upgraded tree code. But eliminating bigger trees now requires developers to plant replacements on-site or pay into a fund that the city plans to utilize to help reforest areas like South Park.

In Seattle's South Park area, residents have about half as much tree canopy as the citywide average. Four single-family homes when stood on this lot, where 22 new units will quickly be developed. Plans filed with the city show three big evergreens and numerous smaller sized trees that are still standing on the lot are slated for removal. Parker Miles Blohm/KNKX hide caption

Groups such as Tree Action Seattle mention that these brand-new trees will take numerous years to mature - sacrificing years of carbon mitigation work when compared to existing mature trees - at a critical time for suppressing planet-warming emissions.

Morris says the trees that will likely be lowered for this development may not appear like a big number.

"This truly is death by a million cuts."

He says trees have actually been reduced all over the city for several years - thousands per year.

"At that scale, the cooling impact of the trees is decreased," states Morris, "and the increased danger of death from extreme heat is increased."

Building codes aren't staying up to date with environment change

Tree loss is not restricted to Seattle. It's occurring in lots of cities across the country, from Portland, Ore., to Charleston, W.Va., and Nashville, Tenn., states Portland State University location teacher Vivek Shandas. "If we don't take swift and really direct action with conservation of trees, of existing canopy, we're visiting the whole canopy diminish," Shandas says.

He states present community codes don't sufficiently attend to the ramifications of environment change. The Pacific Northwest, Shandas says, ought to be preparing for progressively hot summertimes and more extreme rain in winter. Trees are required to supply shade and soak up runoff.

"So that development going in - if it's lot edge to lot edge - we're visiting an amplification of urban heat," Shandas says. "We're going to see a higher quantity of flooding in those areas."

Climate modification is magnifying typhoons and raising water level while also playing a role in wildfires. Such extreme conditions are exceeding structure codes, explains Shandas, and he fears this will occur in the Northwest too.

Shandas says how developers react to the building codes that Seattle embraces over the next 20 to 50 years will identify the degree to which trees will help individuals here adapt to the warming environment.

That matters in Seattle, where the nights aren't cooling off nearly as much as they used to and where typical daytime highs are getting hotter every year.

The Bryant Heights development is a contemporary mix of homes, town homes, single-family homes and retail. Architects Ray and Mary Johnston dealt with the designer to position 86 housing systems where there were initially four. Parker Miles Blohm/KNKX hide caption

An option in the style

Architects Ray and Mary Johnston see part of the option at another Seattle development they designed around an existing 40-year-old Scotch pine.

The Boulders development, near Seattle's Green Lake Park, transformed a single-family lot into a complex with 9 town homes. The designer included fully grown trees he restored from other developments - transplanting them tactically to include texture and cooling to the landscaping.

Mary Johnston says building with trees in mind could likewise help individuals's wallets. Boulders, she states, is an example. "Since these units have air conditioning, those costs are going to be lower because you have this type of cooler environment," she states. Ray Johnston states locations like this dubious city sanctuary ought to be incentivized in city codes, especially as climate change continues.